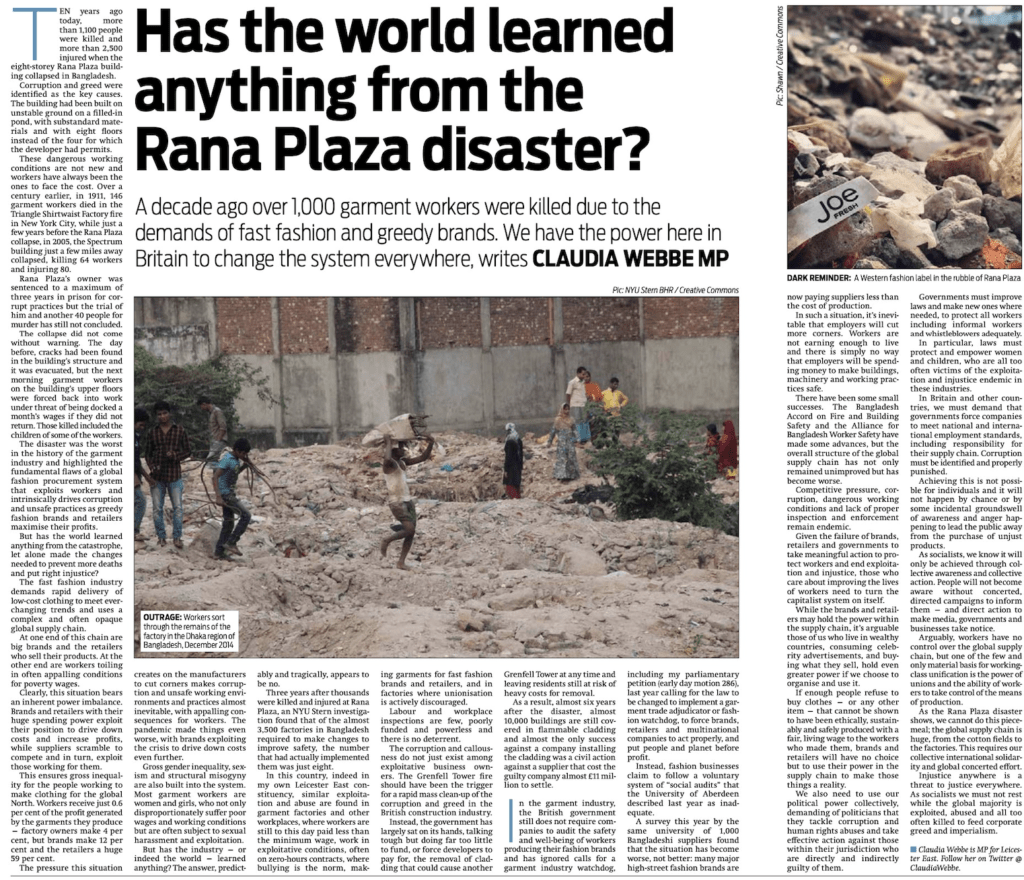

Has the world learned anything from the Rana Plaza Disaster?

By Claudia Webbe MP

A decade ago over 1,000 garment workers were killed due to the demands of fast fashion and greedy brands. We have the power here in Britain to change the system everywhere, writes CLAUDIA WEBBE MP.

Ten years ago today, more than 1,100 people were killed and more than 2,500 injured when the eight-storey Rana Plaza building collapsed in Bangladesh.

Corruption and greed were identified as the key causes. The building had been built on unstable ground on a filled-in pond, with substandard materials and with eight floors instead of the four for which the developer had permits.

These dangerous working conditions are not new and workers have always been the ones to face the cost. Over a century earlier, in 1911, 146 garment workers died in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in New York City, while just a few years before the Rana Plaza collapse, in 2005, the Spectrum building just a few miles away collapsed, killing 64 workers and injuring 80.

Rana Plaza’s owner was sentenced to a maximum of three years in prison for corrupt practices but the trial of him and another 40 people for murder has still not concluded.

The collapse did not come without warning. The day before, cracks had been found in the building’s structure and it was evacuated, but the next morning garment workers on the building’s upper floors were forced back into work under threat of being docked a month’s wages if they did not return. Those killed included the children of some of the workers.

The disaster was the worst in the history of the garment industry and highlighted the fundamental flaws of a global fashion procurement system that exploits workers and intrinsically drives corruption and unsafe practices as greedy fashion brands and retailers maximise their profits.

But has the world learned anything from the catastrophe, let alone made the changes needed to prevent more deaths and put right injustice?

The fast fashion industry demands rapid delivery of low-cost clothing to meet ever-changing trends and uses a complex and often opaque global supply chain.

At one end of this chain are big brands and the retailers who sell their products. At the other end are workers toiling in often appalling conditions for poverty wages.

Clearly, this situation bears an inherent power imbalance. Brands and retailers with their huge spending power exploit their position to drive down costs and increase profits, while suppliers scramble to compete and in turn, exploit those working for them.

This ensures gross inequality for the people working to make clothing for the global North. Workers receive just 0.6 per cent of the profit generated by the garments they produce — factory owners make 4 per cent, but brands make 12 per cent and the retailers a huge 59 per cent.

The pressure this situation creates on the manufacturers to cut corners makes corruption and unsafe working environments and practices almost inevitable, with appalling consequences for workers. The pandemic made things even worse, with brands exploiting the crisis to drive down costs even further.

Gross gender inequality, sexism and structural misogyny are also built into the system. Most garment workers are women and girls, who not only disproportionately suffer poor wages and working conditions but are often subject to sexual harassment and exploitation.

But has the industry — or indeed the world — learned anything? The answer, predictably and tragically, appears to be no.

Three years after thousands were killed and injured at Rana Plaza, an NYU Stern investigation found that of the almost 3,500 factories in Bangladesh required to make changes to improve safety, the number that had actually implemented them was just eight.

In this country, indeed in my own Leicester East constituency, similar exploitation and abuse are found in garment factories and other workplaces, where workers are still to this day paid less than the minimum wage, work in exploitative conditions, often on zero-hours contracts, where bullying is the norm, making garments for fast fashion brands and retailers, and in factories where unionisation is actively discouraged.

Labour and workplace inspections are few, poorly funded and powerless and there is no deterrent.

The corruption and callousness do not just exist among exploitative business owners. The Grenfell Tower fire should have been the trigger for a rapid mass clean-up of the corruption and greed in the British construction industry.

Instead, the government has largely sat on its hands, talking tough but doing far too little to fund, or force developers to pay for, the removal of cladding that could cause another Grenfell Tower at any time and leaving residents still at risk of heavy costs for removal.

As a result, almost six years after the disaster, almost 10,000 buildings are still covered in flammable cladding and almost the only success against a company installing the cladding was a civil action against a supplier that cost the guilty company almost £11 million to settle.

In the garment industry, the British government still does not require companies to audit the safety and well-being of workers producing their fashion brands and has ignored calls for a garment industry watchdog, including my parliamentary petition (early day motion 286), last year calling for the law to be changed to implement a garment trade adjudicator or fashion watchdog, to force brands, retailers and multinational companies to act properly, and put people and planet before profit.

Instead, fashion businesses claim to follow a voluntary system of “social audits” that the University of Aberdeen described last year as inadequate.

A survey this year by the same university of 1,000 Bangladeshi suppliers found that the situation has become worse, not better: many major high-street fashion brands are now paying suppliers less than the cost of production.

In such a situation, it’s inevitable that employers will cut more corners. Workers are not earning enough to live and there is simply no way that employers will be spending money to make buildings, machinery and working practices safe.

There have been some small successes. The Bangladesh Accord on Fire and Building Safety and the Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety have made some advances, but the overall structure of the global supply chain has not only remained unimproved but has become worse.

Competitive pressure, corruption, dangerous working conditions and lack of proper inspection and enforcement remain endemic.

Given the failure of brands, retailers and governments to take meaningful action to protect workers and end exploitation and injustice, those who care about improving the lives of workers need to turn the capitalist system on itself.

While the brands and retailers may hold the power within the supply chain, it’s arguable those of us who live in wealthy countries, consuming celebrity advertisements, and buying what they sell, hold even greater power if we choose to organise and use it.

If enough people refuse to buy clothes — or any other item — that cannot be shown to have been ethically, sustainably and safely produced with a fair, living wage to the workers who made them, brands and retailers will have no choice but to use their power in the supply chain to make those things a reality.

We also need to use our political power collectively, demanding of politicians that they tackle corruption and human rights abuses and take effective action against those within their jurisdiction who are directly and indirectly guilty of them.

Governments must improve laws and make new ones where needed, to protect all workers including informal workers and whistleblowers adequately.

In particular, laws must protect and empower women and children, who are all too often victims of the exploitation and injustice endemic in these industries.

In Britain and other countries, we must demand that governments force companies to meet national and international employment standards, including responsibility for their supply chain. Corruption must be identified and properly punished.

Achieving this is not possible for individuals and it will not happen by chance or by some incidental groundswell of awareness and anger happening to lead the public away from the purchase of unjust products.

As socialists, we know it will only be achieved through collective awareness and collective action. People will not become aware without concerted, directed campaigns to inform them — and direct action to make media, governments and businesses take notice.

Arguably, workers have no control over the global supply chain, but one of the few and only material basis for working-class unification is the power of unions and the ability of workers to take control of the means of production.

As the Rana Plaza disaster shows, we cannot do this piecemeal; the global supply chain is huge, from the cotton fields to the factories. This requires our collective international solidarity and global concerted effort.

Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. As socialists we must not rest while the global majority is exploited, abused and all too often killed to feed corporate greed and imperialism.

Claudia Webbe MP is the member of Parliament for Leicester East. You can follow her at www.facebook.com/claudiaforLE and twitter.com/ClaudiaWebbe