Windrush 75 – the fight to honour a generation’s legacy is still far from over

By Claudia Webbe MP

The government’s obfuscation, evasiveness and delay since the Windrush scandal was exposed makes clear that those in power cannot be trusted to do the right thing, says CLAUDIA WEBBE MP

THIS week marks the 75th anniversary of the arrival of the Empire Windrush at Tilbury Dock on June 22 1948, which started the process, which continued until 1971, of pioneers from all over the Caribbean paving the way to support and meet the needs of a nation recovering from war.

Britain invited them to help in the aftermath of World War II, and in solidarity they came.

My own family were among that generation. My parents arrived from the Caribbean Island of Nevis and settled in Leicester and, like others of their generation, made huge sacrifices to build the Britain we know today.

The arrival of the Windrush generation was not just vital for the history of black communities, but for the whole of Britain.

It emboldens black history as British history, and its lessons are important for all of us.

But this week also marks 75 years of discrimination and scandal. Within a few years British firms would be actively seeking overseas workers from the Caribbean and elsewhere, but when the Windrush first docked, then-secretary of state for the colonies Sir Arthur Creech Jones wrote a Cabinet memorandum noting that the British government was strongly opposed to immigration.

Tragically, that opposition and the racism that underlies it has persisted now for generations.

The Windrush scandal brought the issue of the Conservative government’s 2012 “hostile environment” policy to the public’s attention in 2018.

Under the policy, landlords, employers, service providers, banks, schools and other institutions became state-sanctioned immigration enforcement officers.

The policy led to many of the Windrush generation who came in the ’50s and ’60s as children, without documentation, being classed as “illegal immigrants” and denied access to medical care, benefits, housing and employment.

Many have been detained and even deported, despite having lived in Britain for most of their lives. Many lost their homes and livelihoods. They lived in fear and were frightened, they hid and they struggled to survive.

Their mistreatment, through no fault of their own, had a significant impact on their mental health, causing stress, anxiety and depression.

The attitudes that underlie this discriminatory and oppressive policy that disproportionately impacted people of the Caribbean are deeply rooted in the colonial mindset that persists among the political, corporate and media elite.

The “naked violence” of colonialism that Frantz Fanon identified may have metamorphosed at least partly into a subtler form, but his principle that it must be met with equally resolute resistance applies as much now as when he wrote it.

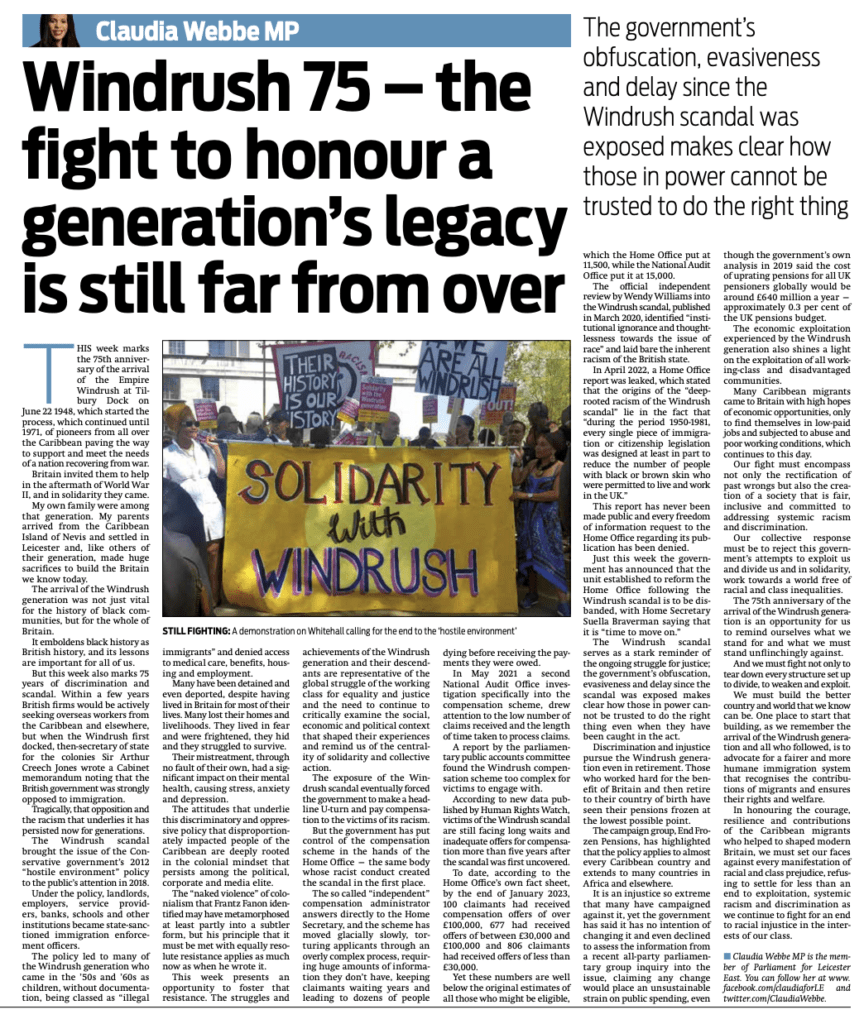

This week presents an opportunity to foster that resistance. The struggles and achievements of the Windrush generation and their descendants are representative of the global struggle of the working class for equality and justice and the need to continue to critically examine the social, economic and political context that shaped their experiences and remind us of the centrality of solidarity and collective action.

The exposure of the Windrush scandal eventually forced the government to make a headline U-turn and pay compensation to the victims of its racism.

But the government has put control of the compensation scheme in the hands of the Home Office — the same body whose racist conduct created the scandal in the first place.

The so called “independent” compensation administrator answers directly to the Home Secretary, and the scheme has moved glacially slowly, torturing applicants through an overly complex process, requiring huge amounts of information they don’t have, keeping claimants waiting years and leading to dozens of people dying before receiving the payments they were owed.

In May 2021 a second National Audit Office investigation specifically into the compensation scheme, drew attention to the low number of claims received and the length of time taken to process claims.

A report by the parliamentary public accounts committee found the Windrush compensation scheme too complex for victims to engage with.

According to new data published by Human Rights Watch, victims of the Windrush scandal are still facing long waits and inadequate offers for compensation more than five years after the scandal was first uncovered.

To date, according to the Home Office’s own fact sheet, by the end of January 2023, 100 claimants had received compensation offers of over £100,000, 677 had received offers of between £30,000 and £100,000 and 806 claimants had received offers of less than £30,000.

Yet these numbers are well below the original estimates of all those who might be eligible, which the Home Office put at 11,500, while the National Audit Office put it at 15,000.

The official independent review by Wendy Williams into the Windrush scandal, published in March 2020, identified “institutional ignorance and thoughtlessness towards the issue of race” and laid bare the inherent racism of the British state.

In April 2022, a Home Office report was leaked, which stated that the origins of the “deep-rooted racism of the Windrush scandal” lie in the fact that “during the period 1950-1981, every single piece of immigration or citizenship legislation was designed at least in part to reduce the number of people with black or brown skin who were permitted to live and work in the UK.”

This report has never been made public and every freedom of information request to the Home Office regarding its publication has been denied.

Just this week the government has announced that the unit established to reform the Home Office following the Windrush scandal is to be disbanded, with Home Secretary Suella Braverman saying that it is “time to move on.”

The Windrush scandal serves as a stark reminder of the ongoing struggle for justice; the government’s obfuscation, evasiveness and delay since the scandal was exposed makes clear how those in power cannot be trusted to do the right thing even when they have been caught in the act.

Discrimination and injustice pursue the Windrush generation even in retirement. Those who worked hard for the benefit of Britain and then retire to their country of birth have seen their pensions frozen at the lowest possible point.

The campaign group, End Frozen Pensions, has highlighted that the policy applies to almost every Caribbean country and extends to many countries in Africa and elsewhere.

It is an injustice so extreme that many have campaigned against it, yet the government has said it has no intention of changing it and even declined to assess the information from a recent all-party parliamentary group inquiry into the issue, claiming any change would place an unsustainable strain on public spending, even though the government’s own analysis in 2019 said the cost of uprating pensions for all UK pensioners globally would be around £640 million a year — approximately 0.3 per cent of the UK pensions budget.

The economic exploitation experienced by the Windrush generation also shines a light on the exploitation of all working-class and disadvantaged communities.

Many Caribbean migrants came to Britain with high hopes of economic opportunities, only to find themselves in low-paid jobs and subjected to abuse and poor working conditions, which continues to this day.

Our fight must encompass not only the rectification of past wrongs but also the creation of a society that is fair, inclusive and committed to addressing systemic racism and discrimination.

Our collective response must be to reject this government’s attempts to exploit us and divide us and in solidarity, work towards a world free of racial and class inequalities.

The 75th anniversary of the arrival of the Windrush generation is an opportunity for us to remind ourselves what we stand for and what we must stand unflinchingly against.

And we must fight not only to tear down every structure set up to divide, to weaken and exploit.

We must build the better country and world that we know can be. One place to start that building, as we remember the arrival of the Windrush generation and all who followed, is to advocate for a fairer and more humane immigration system that recognises the contributions of migrants and ensures their rights and welfare.

In honouring the courage, resilience and contributions of the Caribbean migrants who helped to shaped modern Britain, we must set our faces against every manifestation of racial and class prejudice, refusing to settle for less than an end to exploitation, systemic racism and discrimination as we continue to fight for an end to racial injustice in the interests of our class.

Claudia Webbe MP is the member of Parliament for Leicester East. You can follow her at www.facebook.com/claudiaforLE and twitter.com/ClaudiaWebbe